Is the SCOTUS partisan? Data Science approach.

With current polarization of the political life in the United States one of the common accusation we can see both in mass media and social media is that the Supreme Court of the United States is extremely partisan. This generally means that the Justices of the Supreme Court render decisions along party lines rather than based on the merits of the case or the actual meaning of the Constitution. But is that true and was it always the case?

Data Collection

In order to analyze this question, I collected some data about the compositions of the court and the voting outcome for the cases that this court decided. Cases organized by Justices and their votes can be found here. This file contains detailed information about each case decided by the SCOTUS from 1946 to 2023 including which Justice voted which way (with the majority or dissented). I also manually scraped the data about Justices from the covered period of data. For each Justice in the list of all Justices I identified the party affiliation of the judge. The implicit assumption about the SCOTUS nominations and confirmed Justices is that they are supposed to be non-partisan and impartial. However, the question that we are trying to analyze is to what extent the accusations of partisanship are substantiated. Therefore, I will be using the party affiliation of the President who nominated a judge as a proxy for the party affiliation of that judge.

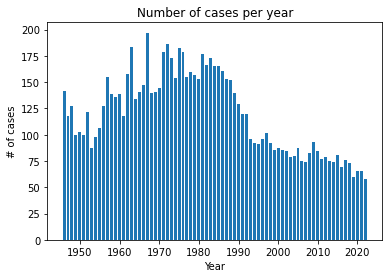

We can see that the total number of decided cases is going down since 1980s to about 60-70 per year. The reason for this decline in productivity is unclear and frankly is out of the scope of this post.

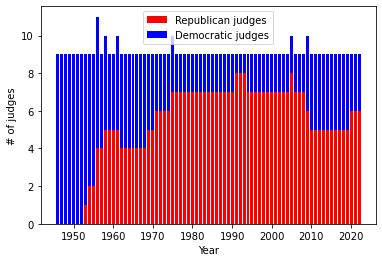

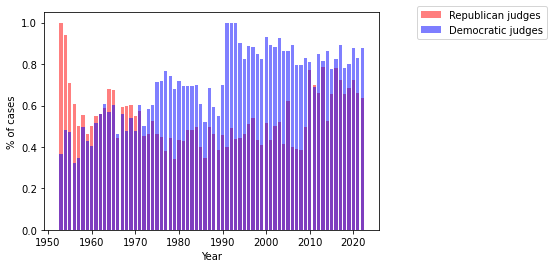

We can look at the composition of the court now.

In 1946-1952 all of the judges on the highest bench in the country were appointed by Democratic Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman. Starting with Chief Justice Earl Warren nominated by Dwight D. Eisenhower Republican Justices quickly increased in number and since 1970s have never been in the minority. Few cases when the total number was over 9 is due to years when both an outgoung (retiring or deceased) and newly appointed Justices were active during the same year.

Voting Pattern Analysis

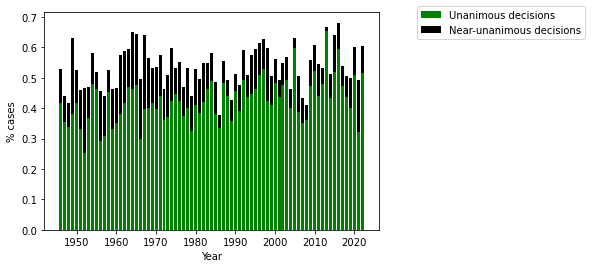

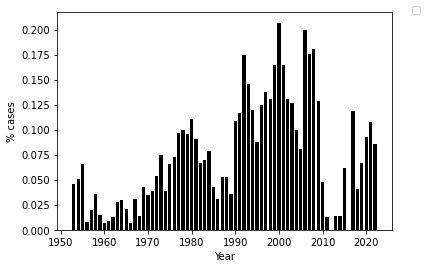

First, we can look at how many of the cases are decided unanimously or near-unanimously (with one dissenting judge).

From 30% to 45% of cases do not cause any major split in opinions. If we add the near-unanimous decisions where one judge was not persuaded by the majority decision, we estimate that easily half of the cases are decided based on consensus. Which already indicates that if there is a level of partisanship in the decision making it is not very high. Before we look any further we can check who is that lone dissenter.

Turns out, on average it can be anyone: both Republican and Democratic Justices can be a lonely voice of the opposition. Two notable deviations from this rule: before 1953 there was no Republican judges on the bench to dissent, and there is also an unexplained dip in the middle of 1980s. One would think that when Democratic judges are vastly overnumbered by Republican judges we would see more dissents from the Democratic Justices but that is not the case.

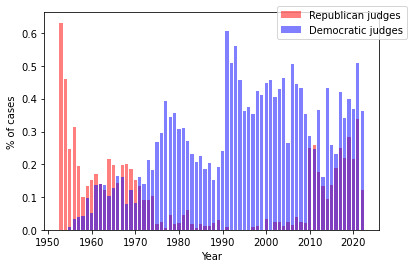

But let’s look further, what if the other half of the cases is decided exclusively along party lines. We are interested in how many cases all judges with the same affiliation vote together (we only consider years from 1953 when there was more than one party represented).

We can see that Democratic judges used to vote together much more than conservative judges in 1970-2010. In early 1990s on all the cases Democratic judges were united (which is not very surprising since there were only two of them). After 2010 levels are roughly the same. But we have to adjust for unanomous decisions as well: in these all judges vote together but not along the party lines.

Trends are similar albeit smaller in absolute values. Which again is not surprising since roughly from the same time conservative judges were in an uninterrupted majority and there were only two liberal judges (or sometimes even one). One thing to notice is the drastic increase in conservative unanimity starting from 2010 which somewhat aligns with the increase in polarization of the politics and society.

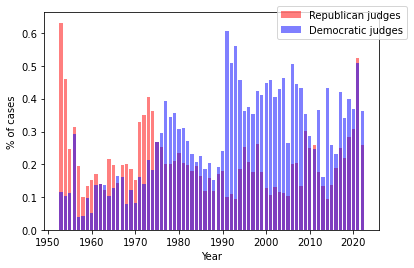

Now, if we assume some sort of partisanship in decisions, clearly whenever there is an imbalance of more than 5:4 to one of the sides, judges from the larger group can feel less pressured to vote in line with other judges from the same group. They can dissent without compromising the desired outcome. We can adjust for such cases by adding cases where one out of 6 or 7 judges of the majority group dissented.

We can see that the gap between parties narrowed down: in a lot of cases each party votes together to win while leaving some leaway for one of them to dissent without changing the majority decision. However, again, liberal judges seem to vote together more often than conservative judges. But how often do they vote against each other? We can look at the cases when the vote split happened exactly along party lines.

Turns out, this does not happen very often: only around 10% of cases are decided that way. More interestingly, this happens more often when the imbalance in court composition is higher: the dip in 2010s aligns with the time when the court was 4:5 liberal vs. conservative Justices.

Individual Voting Patterns

As an additional excercise, we can look at individual voting patterns of different Justices. For example, we can check which of the judges agrees with the majority most often or least often.

| Justice | % cases | Justice | % cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kavanaugh | 93.9 | Douglas | 71.3 | |

| Kennedy | 91.7 | Marshall | 72.0 | |

| Barrett | 90.8 | Harlan | 72.0 |

Justice Kavanaugh is the most agreeable judge on the bench so far while William O. Douglas was the most disagreeable over his record long 36.6 year long tenure. Coincidentally, William O. Douglas and John Marshall Harlan II are the judges that were the most often lone dissenting voices in their cases. On the opposite, Kavanaugh, Kagan, Barrett, and Goldberg never dissented from the unanimous majority.

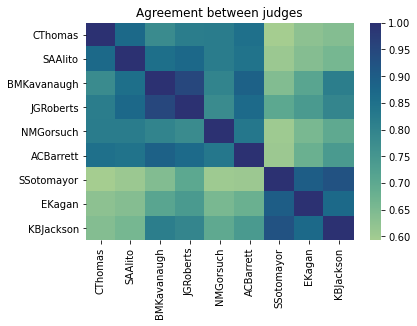

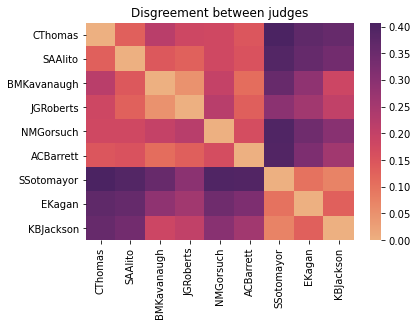

When it comes to agreement between individual judges, the highest level of agreement is between Kavanaugh and Roberts who agree on 95% of the cases in front of them. On the opposite end of the spectrum, judges Douglas and Rehnquist disagreed on 57% of the cases.

Finally, if we look at the percentage of agreement and disagreement for the current Supreme Court, we can clearly see a division between the liberal and conservative Justices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can see that even though in the recent years the amount of partisan voting among Supreme Court Justices increased, it is not as prevalent as people might think. The impression of partisanship is likely stemming from a small number of very politicized cases such as Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that are intensively covered by media.